I was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which remains an exotic place to me because my family moved east to Burlington, Ontario when I was just a year old. We lived near Indian Point, a few houses from Lake Ontario, right across the Hamilton bay from the fiery smokestacks of the now-shuttered steel plants. Watching the smoke billow up into the sky through our neighbour’s binoculars was my first impression of the Rest of the World.

I was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which remains an exotic place to me because my family moved east to Burlington, Ontario when I was just a year old. We lived near Indian Point, a few houses from Lake Ontario, right across the Hamilton bay from the fiery smokestacks of the now-shuttered steel plants. Watching the smoke billow up into the sky through our neighbour’s binoculars was my first impression of the Rest of the World.

There was no one my age on Stillwater Crescent, my older brother was at school, and so (as children did then) I roamed the ravines of Indian Point on my own, or with one of our several dogs. My brother and I actually did find arrowheads in the former stomping grounds of Chief Joseph Brant. And I am just old enough to remember feeding apples to the horse that brought the ice-wagon down our street on summer days.

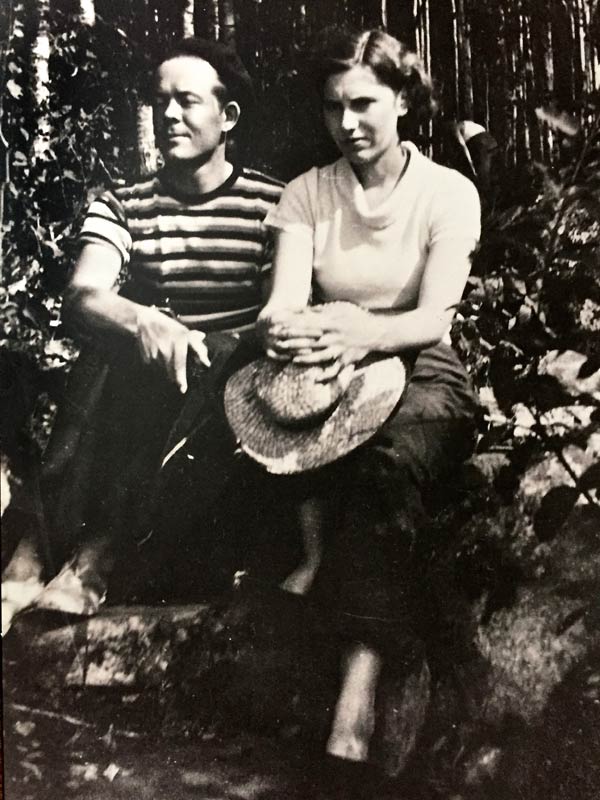

My father, Clyde Jackson, was a civil engineer who was transferred from Saskatoon to Burlington in order to oversee the construction of a new water-treatment plant. He drove home from the office for lunch every day, and every day my mother put three meals on the table, including two desserts. Chocolate pudding with a faintly rubbery skin was my favourite.

A university graduate (math and home economics), Olive Jackson brought endless, often subversive creativity to her role as wife, home-maker and mother to her three children, one born every seven years.

In his teens and twenties, my father was a gifted cartoonist and artist who quickly determined that drawing pin-up girls would not support a prairie family through the Depression. So he became a civil engineer. Upon graduation from the University of Saskatchewan, he worked on the epic construction of the Broadway Bridge, a Depression relief project and now a defining icon of Saskatoon. This first job remained a proud memory for him.

In his teens and twenties, my father was a gifted cartoonist and artist who quickly determined that drawing pin-up girls would not support a prairie family through the Depression. So he became a civil engineer. Upon graduation from the University of Saskatchewan, he worked on the epic construction of the Broadway Bridge, a Depression relief project and now a defining icon of Saskatoon. This first job remained a proud memory for him.

In her married life, my mother painted, sculpted, sewed with couturier flair, and had a journalist’s drive to learn—about nutrition, medicine, and the arts. Both my parents were raised in poor families: Clyde lost his father to TB at the age of 12, and his mother raised her three kids by teaching piano. My grandfather on my mother’s side sold farm equipment, and the family ran a boarding house in Saskatoon. They were both the first in their families to graduate from college. They never took for granted the privileges of their post-war, middle-class life during that briefly stable phase of the planet. My brother and sister and I grew up in the golden age of the nuclear family, where parents had hobbies, took family road trips, drank Manhattans, rented summer cottages, and lived on a single income.

We won’t see that again.

We moved from the lakeshore closer to downtown so I could go to school—Burlington Central. My sister Jori was born when I was 7 and two years later my brother Bruce suffered a terrible injury when a home-made rocket he had devised exploded, almost killing him. I was blithely unaware of what they endured as he underwent dozens of surgeries.

We moved from the lakeshore closer to downtown so I could go to school—Burlington Central. My sister Jori was born when I was 7 and two years later my brother Bruce suffered a terrible injury when a home-made rocket he had devised exploded, almost killing him. I was blithely unaware of what they endured as he underwent dozens of surgeries.

High school (Burlington Central, again) was just up the street. My girlfriend Diane and I walked the three blocks to school carrying our textbooks and binders in our arms, in those pre-knapsack, pre-Nike days. Burlington was still a leafy small town with one main street and no malls. The big adventure on weekends was to walk the length of Brant St., down to the Dairy Queen and back, and maybe get a few catcalls from boys driving by.

My first 45 record was Tab Hunter singing Red Sails in the Sunset, followed closely by Little Richard’s Tutti-Frutti. Wednesday nights I watched I Love Lucy, Carol Burnett, and the Gary Moore show. Every spring, Burlington smelled like ketchup because Heinz had a canning factory there. Another factory made wooden fruit baskets. As kids we played in the apple orchards, and roamed up and down the shores of Rambeau Creek, sometimes catching carp. But it was less bucolic than it sounds, as suburbia bloomed and the orchards shrank.

As long as we were home for dinner nobody cared where we went. Nobody drove us to Brownies, and nothing bad ever happened to us. (As I edge into memoir here, it’s worth mentioning that two of my books cover some of this personal history, in The Mother Zone and Home Free.)

Was I a writer in high school? A little bit. I sent one lugubrious poem to a university literary magazine, which got accepted. It was called Compliance, a correctly executed sonnet (and a good note to self, unheeded.) I wrote for Runes, the high school literary magazine, and worked on the ambitious yearbook. My mother sewed a lot of my clothes, something she excelled at. A pink silk shantung prom dress, a teal-blue peau de soi semi-formal, a black sheath with spaghetti straps and a curious raffia trim. I remember them well.

I was self-conscious about my body from an early age, I don’t know why, I was a perfectly average height and weight. As was the custom for many teenage girls at the time, I wore panty girdles, every day. Over panties. Ridiculous! And padded bras, and slips, and half-slips, and stiff crinolines, and garter belts—a veritable Smithsonian of underwear. Woe betide the poor boy who tried to wedge a finger under the thigh-long elastic cuff of the panty girdle.

My girlfriends and I dated in high school, but it was all very tame; a walk to the Roxy movie theatre to see Cimarron, maybe a Tin Roof sundae afterwards. It sounds 19th century, but this was actually 1960, when phones had tails, cars had fins, and the wildest transgression I can remember is stealing liquor from a parental cabinet before heading off to a Young People’s meeting at the United Church. My family still went to church, an occasion I associate with wearing hats and nylon stockings.

There were wilder girls, I knew. I wasn’t one of them. I read poetry, and put scarves over the rec room lamp to listen to Johnny Mathis sing “Chances Are”. I was both precocious and pretentious, preferring jazz to pop—Charlie Mingus, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington. I played the piano. At 16 I discovered Existentialism, and took to reading Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. I felt moody and superior as a result.

During the summers I worked at a YMCA camp in Georgian Bay, called Wabanaki. This is where I ‘discovered’ both epic nature, and the warmth of community. I wasn’t aware of how solitary my childhood had been until I went to camp and learned how to be with other people my age. Georgian Bay is one of the most beautiful places on earth, and Wabanaki was situated on the great wide rocky plates of the Canadian Shield— a powerful landscape that I absolutely fell in love with. Every day at lunch, at girls’ camp, we sang our lungs out, and that was like gospel to me. I graduated from camper to counsellor, and took my own campers out on three-day canoe trips, to Go Home Bay and back.

One summer I fell in love with a boy from a neighbouring camp, Kitchekewana. Staying out late at night, on the big rocks, under the stars, with all the mosquitos. Hard to beat that. My boyfriend went off to university, a different one from Victoria College, where I had been accepted in the English Literature program. We lasted two more years.

Victoria College had an impressive English Literature faculty that included the critic Northrop Frye, the poet Jay Macpherson, poet and publisher-to-be Dennis Lee, and, across the campus, the maverick media genius Marshall McLuhan. I remember stepping over McLuhan’s very long legs when he was giving a seminar in the house where I was living, and I can still see the great domed forehead of Northrop Frye as he tilted his way across the campus. Frye taught Religious Knowledge 101. He listened strenuously in class, and reflected for long moments whenever one of us asked a question. Dennis Lee (who would soon leave academia to help launch Rochdale, a doomed independent university, and the still-thriving publishing venture, House of Anansi) taught me drama and poetry—including Canadian poetry.

Like the Canadian Shield of Georgian Bay, poets like Leonard Cohen, Al Purdy, P.K. Page and Margaret Atwood (who began as a poet) offered another homecoming for me—writing that reflected my own landscapes and history. I didn’t realize how rare this was, to have professors and mentors who rejected the post-colonial mentality that still defined Canadian culture. After graduation, I was lucky to cross paths with other adventurous young authors who would go on to transform Canadian writing and publishing. Thanks to them, I took it for granted that my own experience, my own neighbourhoods, were worth writing about—perhaps the most valuable lesson a young writer can receive.

This was the late nineteen-sixties, when so much was in flux: the birth control pill had arrived, I watched Grace Slick sing “White Rabbit”, Bob Dylan snarled his way into our consciousness. Sex, drugs and rock’n’ roll: this was when all three rolled into town. I wasn’t a big fan of drugs and fancied myself more bohemian than hippie. But no one I knew talked about careers or marriage or settling down. We were “exploring consciousness”, travelling on a dime, and turning away from the bourgeois comforts and values we had been brought up with.

In the process, we puzzled and disappointed our parents. We left for Europe, or India, or South America, or all three. We lived in caves on Crete. Some friends went on to grad school; that was the last thing I wanted to do. In university, I also lost a grip on who I was, and struggled some with anxiety, depression and questions of identity. I didn’t have proper names for that particular fog, at the time. As for a vocation, I had only vague ideas about going “into publishing”, or perhaps working for a newspaper. Writing was one option, but nothing urgent, yet. Mostly I was busy being a girlfriend, embarking on adventures, and identifying with Sylvia Plath.

In my twenties, I lived on five successive streets in Toronto’s Annex: Spadina Ave., Robert St., Major St., and Brunswick Avenue. I lived at 671 Spadina Ave. when it became the home base for the House of Anansi, one of the country’s first writer-run publishing houses. For a brief time I worked as an assistant to one of the founders, Dennis Lee. Coach House was around the corner, and two blocks over, another indie house sprang up, called new press. I lived on the third floor of that Victorian building too. I wasn’t really writing yet, but I was living in an atmosphere of writing and publishing. I took my time coming into my own as a writer. I think the first piece I published was in that venerable, now extinct journal, the Canadian Forum. It was a story about The Whole Earth Catalogue, brainchild of Ur-hippie/visionary Stewart Brand. Another early piece was about the social minuet that takes place among strangers in a city Laundromat (the one across from 671 Spadina, in fact).

Subcultures attracted me, and in the nineteen sixties, subcultures were everywhere.

At first I used freelance writing as a way to subsidize my travel. I wrote about canoeing in Temagami for Outside magazine, and I tagged along on an expedition to prove that the lost city of Atlantis was submerged just off the shore of a Bahamian island. I embarked on a five-month bicycle trip from Mexico to Peru with my cyclist boyfriend, and wrote about that doomed adventure for Outside too.

I wrote about marlin fishing near Bimini, for the late, great Saturday Night magazine. It was the 1970’s, the golden age of magazine writing, and editors might send you exotic places for weeks, just to soak up “colour”. I wrote about the rock’n’roll legend Ronnie Hawkins for Rolling Stone. I had a fine old time, until, in my early thirties, I got tired of life as a professional outsider (including being on the road with a professional Italian cycling team). I wanted to settle down, have a regular pay cheque, and maybe think about a family. The fact that my boyfriend (and husband to be) had put his career as a journalist on pause in order to play the congas in a rock band also made job security appealing.

I was hired as an associate editor at Canada’s newsmagazine, Maclean’s, just when it was going weekly. There I met and worked with people who would remain my friends for life, but I was still restless, eager to write something of my own. Within a year I quit my lovely job to complete a collection of stories that I pitched to Farrar, Straus & Giroux. I went to New York and literally threw my manuscript over the transom—they did have one. The editors wrote me a very encouraging rejection, and suggested I acquire an agent. But then some combination of inertia, depression and love troubles prevented me from finishing the book.

I drifted. I moved in with my boyfriend. I reviewed books. Then I got involved with a trio of feminist performers collectively known as The Clichettes.

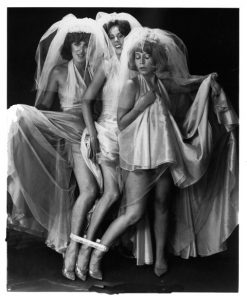

The Clichettes were choreographers who did lip-sync, art-directed versions of old Motown hits, while dressed in bridal gowns, go-go boots and outsize beehive wigs. They took great songs by the Ronettes or the Supremes and turned them into satirical mini-manuals for How to Be A Girl. They were putting together some of these wildly popular performances into a show, with a storyline—did I want to come on board as their co-writer?

That was the start of five years working with the Clichettes on two of their shows—Half Human, Half Heartache, and She-Devils of Niagara. Half Human established the premise (The Clichettes as space aliens who must learn feminine behavior to disguise themselves as earth girls), and the cabaret show was a big hit in Toronto, with productions that followed in Ottawa and Vancouver. Our next endeavour, She-Devils of Niagara, was a more ambitious stage show in a regular theatre. The Clichettes were cast in a dystopian future where gender was strictly regulated, and history had been banished to the basement of a wax museum in Niagara Falls. The Clichettes went on to produce more wildly original shows (in one they portrayed various items of furniture, including a bean-bag chair) and I turned my focus (such as it was) to writing books.

At this point, I had a highly energetic two year old son, Casey, and my partner Brian Johnson was freelancing, and writing film reviews for Maclean’s, my former employer. Brian would soon become the senior entertainment writer and film critic for the magazine, for the next 28 years.

Our early years as a family became the subject of my first nonfiction book, The Mother Zone.