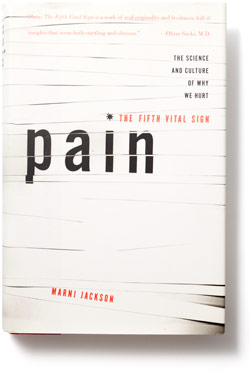

“Pain is a work of real originality and freshness, full of insights that seem both startling and obvious.”

— Oliver Sacks, M.D.

“Pain is a work of real originality and freshness, full of insights that seem both startling and obvious.”

— Oliver Sacks, M.D.

Why are we, the most medicalized of societies, a culture in pain?

A compulsively readable explorer’s journal of the hidden territory of pain, as profound and insightful as the work of Oliver Sacks and Sherwin Nuland.

A bee sting on the lips was the tiny lance that set Marni Jackson off on a four-year exploration of the many ways in which we suffer. Exiled for an afternoon in the country called pain, she realized that no one had the words to describe her condition although it was as familiar as a headache. A fusion of emotion, nerve and memory, pain inspired only questions.

“Why do we still distinguish between mental pain and physical pain,” she asks, “when pain is always an emotional experience? Why is pain so poorly understood, especially in a century of self-scrutiny? Hasn’t anyone noticed the embarrassing fact that science is about to clone a human being but still can’t cure the pain of a bad back?” North Americans spend $24 billion a year on pain relief while chronic pain is on the rise. If pain is the reason why most people visit the doctor, why are most doctors so bad at addressing the problem of suffering?

Pain: The Fifth Vital Sign dives back into the history of pain and forward into the possibilities of pain genetics, bringing us stories of both people in pain and the pain pioneers: eccentrics and artists, wrestlers and writers, ministers and mothers, psychologists and philosophers, nurses and doctors. Marni Jackson has created a definitive, heartfelt, funny and beguiling portrait of a condition we can’t live with—and can’t live without.

Pain: The Science and Culture of Why We Hurt

Random House, 2002

Something is wrong with how we have educated our doctors on the subject of pain, and we’re beginning to recognize this. Medical schools are adding compulsory pain studies. Hospitals have made the measurement of pain—charting the fifth vital sign—part of patient care. In California, UCLA has established a new science and humanities center, the first of kits kind, where the two disciplines can cross-pollinate. Most cities now have a multidisciplinary pain clinic. Our understand of pain has awakened to an awareness of pain as history in the body. Pain is not the invader but part of our identity, an exiled bit of self. We need to find ways to eliminate suffering, but we also need to become more intimate with pain, for the illumination it can give us.

Perhaps the metaphors should shift from war to the environment. Medicine needs to look at pain not as a foreign invasion but as a kind of environmental problem in the body. Chronic pain is like a toxic spill, with damage that eventually spreads far beyond the original site. Neglect one local disaster—a back injury, a twisted knee—and it can metastasize into more pain. More pain poisons the joy and the vitality of one individual, whose suffering then seeps into the lives of those around them. Pain can destroy a wide radius of lives in the same way that clear-cutting erases the history of a forest. Medicine has to look beyond isolated symptoms and aggressive solutions to the ecology of the larger system.

The body is not the enemy.

***

Opium’s effect on me was immediate and imperative: I must get horizontal now. I oozed onto the floor and stayed there enjoying myself for some time. The Turkish rug had much to tell me, as I recall. Its pattern was intricate and conspiratorial—bottomless, in fact. My companions drifted nearby inside their own happy patterns. After a while, I propped myself up on one elbow and spent a long time drawing a picture of a penis-mushroom entity, from the head of which spewed most of the contents of civilization. I was quite pleased with this. The angles of the room and the corners of my personality had dissolved into a round, warm feeling of immense repose. “An opium high can be described in one word,” writes the novelist Eric Detzler, “comfortable”.